It is widely claimed that microcredit lifts people out of poverty and empowers women. But evidence to support such claims is often anecdotal.

A typical microfinance organisation website paints a picture of very positive impact through stories: “Small loans enable them (women) to transform their lives, their children’s futures and their communities. The impact continues year after year.” Even where claims are based on rigorous evidence, as in a recent article on microfinance in the Guardian by the chief executive officer of CGap, the evidence presented is usually from a small number of chosen single impact evaluations, rather than the full range of available evidence. On the other hand, leading academics such as Naila Kabeer have long questioned the empowerment benefits of microcredit.

So, how do we know if microcredit works? The currency in which policymakers and journalists trade to answer such questions should be systematic reviews and meta-analyses, not single studies. Meta-analysis, which is the appraisal and synthesis of statistical information on programme impacts from all relevant studies, can offer credible answers.

When meta-analysis was first proposed in the 1970s, psychologist Hans Eysenck called it ‘an exercise in mega-silliness’. It still seems to be a dirty word in some policy and research circles, including lately in international development. Some of the concerns about meta-analysis, such as those around pooling evidence from wildly different contexts, may be justified. But others are due to misconceptions about why meta-analysis should be undertaken and the essential components of a good meta-analysis.

3ie and the Campbell Collaboration have recently published a systematic review and meta-analysis by Jos Vaessen and colleagues on the impact of microcredit programmes on women’s empowerment. Vaessen’s meta-analysis paints a very different picture of the impact of microcredit. The research team systematically collected, appraised and synthesised evidence from all the available impact studies. A naïve assessment of that evidence would have indicated that the majority of studies (15 of the 25) found a positive and statistically significant relationship between microcredit and women’s empowerment. The remaining 10 studies found no significant relationship.

So, the weight of evidence based on this vote-count would have supported the positive claims about microcredit. In contrast, Vaessen’s meta-analysis concluded “there is no evidence for an effect of microcredit on women’s control over household spending… (and) it is therefore very unlikely that, overall, microcredit has a meaningful and substantial impact on empowerment processes in a broader sense.” So, what then explains these different conclusions, and in particular, the unequivocal findings from the meta-analysis?

The Vaessen study is a good example of why meta-analysis is highly policy relevant. The meta-analysis process has four distinct phases: calculation of impacts from the studies into policy-relevant quantities, quality assessment of studies, assessment of reporting biases, and synthesis including the possiblestatistical pooling across studies to estimate an average impact. It uses these methods to overcome four serious problems in interpreting evidence from single impact evaluations for decision makers.

First, the size of the impacts found in single studies may not be policy significant. That is, impacts are not sufficiently large in magnitude to justify the costs of delivery or participation. But this information is often not communicated transparently. Thus, many single impact evaluations – and unfortunately a large number of systematic reviews in international development – focus their reporting on whether their impact findings are positive or negative, and not on how big the impact is. This is why an essential component of meta-analysis is to calculate study effect sizes, which measure the magnitude of the impacts in common units. Vaessen’s review concludes that the magnitude of the impacts found in all studies is too small to be of policy significance.

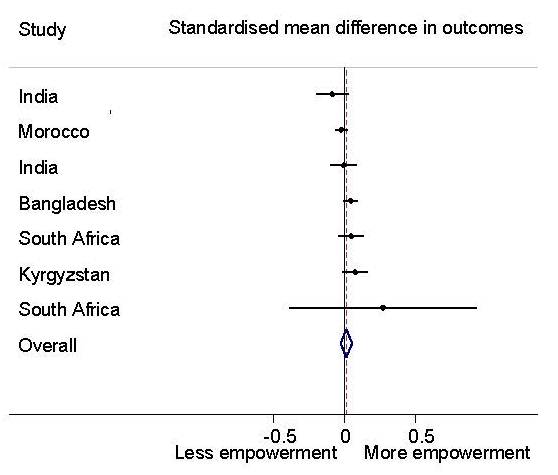

The second problem with single studies is that they are frequently biased. Biased studies usually overestimate impacts. Many microcredit evaluations illustrate this by naïvely comparing outcomes among beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries without accounting for innate personal characteristics such as entrepreneurial spirit and attitude to risk. These characteristics are very likely to be the reason why certain women get the loans and make successful investments. All good meta-analyses critically appraise evidence through systematic risk-of-bias assessment. The Vaessen review finds that 16 of the 25 included studies show ‘serious weaknesses’, and that these same studies also systematically over-estimate impacts. In contrast, the most trustworthy studies (the randomised controlled trials and credible quasi-experiments) do not find any evidence to suggest microcredit improved women’s position in the household in communities in Asia and Africa (see Figure).

The third problem is that the sample size in many impact evaluations is too small to detect statistically significant changes in outcomes – that is, they are under-powered. As noted in recent 3ie blogs by Shagun Sabarwal and Howard White, the problem is so serious that perhaps half of all impact studies wrongly conclude that there is no significant impact, when in fact there is. Meta-analysis provides a powerful solution to this problem by taking advantage of the larger sample size from multiple evaluations and pooling that evidence. A good meta-analysis estimates the average impact across programmes and also illustrates how impacts in individual programmes vary, using what are called forest plots.

The forest plot for Vaessen’s study, presented in the figure, shows an average impact of zero (0.01), as indicated by the diamond, and also shows very little difference in impacts for the individual programmes, as indicated by the horizontal lines which measure the individual study confidence intervals.

There are of course legitimate concerns about how relevant and appropriate it is to pool evidence from different programmes across different contexts. Researchers have long expressed concerns about the misuse of meta-analysis to estimate a significant impact by pooling findings from incomparable contexts or biased results (“junk in, junk out”).

But where evaluations are not sufficiently comparable to pool statistically, for example because studies use different outcomes measures, a good meta-analysis should use some other method to account for problems of statistical power in the individual evaluation studies. Edoardo Masset’s systematic review of nutrition impacts in agriculture programmes assesses statistical power in individual studies, concluding that most studies simply lack the power to provide policy guidance.

In the case of Vaessen’s meta-analysis, which estimates the impacts of micro-credit programmes on a specific indicator of empowerment – women’s control over household spending – the interventions and outcomes were considered sufficiently similar to pool. Subsequent analysis concluded that any differences across programmes were unlikely to be due to contextual factors and much more likely a consequence of reporting biases.

This brings us to the fourth and final problem with single studies, which is that they are very unlikely to represent the full range of impacts that a programme might have. Publication bias, well-known across research fields, occurs where journal editors are more likely to accept findings that are able to prove or disprove a theorem. Conversely, they are less likely to publish studies with null or statistically insignificant findings. The Journal of Development Effectiveness explicitly encourages publication of null findings in an attempt to reduce this problem, but most journals still don’t. In what is possibly one of the most interesting advances in research science in recent years, meta-analysis can be used to test for publication bias. Vaessen’s analysis suggests that publication biases may well be present. But the problems of bias and ‘salami slicing’ in the individual evaluation studies, where multiple publications appeared on the same data and programmes, are also important.

Like all good meta-analyses, the Vaessen review incorporates quality appraisal, the calculation of impact magnitudes and assessment of reporting biases. The programmes and outcomes reported in the single impact evaluations were judged sufficiently similar to pool statistically. By doing this, the review reveals ‘reconcilable differences’ across single studies.

Microcredit and other small-scale financial services may have beneficial impacts for other outcomes, although other systematic reviews of impact evidence (here and here) suggest this is often not the case. But it doesn’t appear to stand up as a means of empowering women.